Edited by Jacy Reese Anthis and Kelly McNamara. Many thanks to the researchers who provided feedback or checked the citations of their work, including Amber E. Boydstun, Robert M. Bohm, Jeffrey L. Kirchmeier, Wayne Sandholtz, Frank R. Baumgartner, Sangmin Bae, and Andrew Hammel. Thanks also to Tom Beggs for discussion on case study methodology.

Abstract

This report aims to assess (1) the extent to which the anti-death penalty movement in the United States, especially from 1966-2015, can be said to have successfully achieved its goals, (2) what factors caused the various successes and failures of this movement, and (3) what these findings suggest about how modern social movements should strategize. The analysis highlights the farmed animal movement as an illustrative example of the strategic implications for a variety of movements. Key findings of this report include that a narrow focus on legal strategies can discourage the growth of a grassroots movement that may be more effective in the longer term and that legislative change is possible without public support.

Table of Contents

Introduction

The US anti-death penalty movement (ADPM) argues that the execution of criminals is immoral or otherwise undesirable. Its advocates therefore support, at least in part, an expansion of the moral circle to encompass convicted criminals, in the sense that they would share the right-to-life of non-convicts. Although there are important differences between the ADPM and farmed animal movement, there is a fundamental similarity between them: Advocates from both movements believe that the sentient beings they seek to protect are granted insufficient consideration, protection, or rights and that it is worth investing time and resources into securing more consideration, protection, or rights for them. Other features that affect the ADPM’s comparability with the farmed animal movement are listed below, but overall it seems that we can glean some strategic insight from the ADPM suitable for effective animal advocacy—that is, evidence on which animal advocacy strategies are most effective.[1]

As with Sentience Institute’s case study of the US anti-abortion movement, this report makes no attempt to evaluate the goals of either movement. This report is exclusively about the strategy of social movements, and while we will discuss goals insofar as they are relevant to strategic discussion, we deliberately avoid any moral assessment.[2]

This report provides a condensed history of the US ADPM with a focus on the 1960s to the present. For comparison, ADPMs in other countries are also considered briefly. After providing this history, the report draws tentative conclusions about which strategies seemed to be most effective for the ADPM and suggests potential implications for social movement strategy. The focus of this report is on strategic insights for the farmed animal movement, but some insights may be useful for other movements as well.

The focus on the US ADPM, rather than on ADPMs in other countries or the broader US prisoners’ rights movement (which includes other goals of prisoner benefit, e.g. better living conditions), was principally due to the greater availability of research and evidence from sociologists, legal scholars, historians, and political scientists. However, compared to the US focus of SI’s case study of the anti-abortion movement,[3] it seemed especially worthwhile to incorporate at least some international comparison on the US ADPM, given that the US has retained the death penalty while 105 other countries have abolished its use.[4] Europe is an especially important comparator because, since the 1970s, around half of the countries that have abolished capital punishment for all crimes have been European countries.[5]

This report was mainly undertaken as exploratory analysis rather than being designed to test explicit hypotheses regarding strategic effectiveness. Nevertheless, the author hoped that the report would provide evidence for or against the claims regarding effective strategy made in SI’s previous two social movement case studies[6] and would provide strategic insight into the foundational questions in effective animal advocacy.[7] As was the case at the start of the author’s research into the US anti-abortion movement, the author believed that the US ADPM had mostly failed at achieving its goals and therefore that this report would provide evidence that, on average, the tactics used by the US ADPM should be avoided by the farmed animal movement.

In several other ways, this report borrows much of the methodology and framing of SI’s previous two social movement case studies.

This report uses the terms capital punishment and death penalty interchangeably, although sometimes it is necessary to distinguish between those sentenced to death and those who are actually executed. Likewise, unless otherwise specified, the terms convict, criminal, and prisoner are used interchangeably, since these groups almost completely overlap in the context of this report. This usage is not intended to deny that some criminals are never convicted or that some prisoners have been wrongly convicted. Unless otherwise specified, the term ADPM is used to encompass both advocates of the total abolition of capital punishment and advocates of a national or statewide moratorium (suspension) on executions, even though some advocates of a moratorium may not support a permanent ban. De jure (legally enforced) abolition is sometimes distinguished from de facto abolition, where executions have ceased in practice but have not been legally banned. The term “grassroots” is used to refer to elements of the movement that include non-professionals, where broad participation is encouraged, and where there is low central control.

Summary of Key Implications

A single historical case study does not provide strong evidence for any general claim on social change strategy; the value of these case studies comes from providing insight into a large number of important questions.[8] This section lists a number of strategic claims supported by the evidence in this report:

- Highly salient judicial changes may provide momentum to opposition groups.

- After controversial Supreme Court rulings, public opinion may move away from the preferences implied by those decisions.

- Social movements should proactively ensure that professionalization and shifts towards legal strategies do not discourage the growth of grassroots efforts (e.g. broad participation, non-professional, decentralized) that may be more effective longer-term.

- Legislative change is surprisingly tractable without public support, though public opinion has a significant effect.

- It is probably easier to introduce and implement unpopular laws if voters in the state do not have ready access to ballot initiatives or referenda.

- Once influential international bodies adopt a value, they may exert pressure on institutions in other parts of the world to adopt the same value.

- Abolition of a practice seems likely to encourage public opinion to gradually turn against that practice.

- Where eliminating a practice is intractable, it may be possible to suspend the practice pending substantial improvements or further research. However, the practice may be subsequently resumed without being substantially challenged.

- Social movements can collaborate to challenge institutions, though collaboration may be temporary or unreliable.

- Social change may be more likely to occur if credible professional groups advocate for change before broader participation and pressure is encouraged.

- As people become more aware of a topic, aggregate attitudes may shift, but polarization may also occur, and legislative change may become less tractable.

- Messaging that includes supplementary arguments attracts broader support. When using supplementary arguments, advocates should focus on issues that seem unlikely to be fixed without abolition of the targeted institution to minimize the risk that they will backfire in the long term.

- The changing tone of media coverage can have significant effects on public opinion.

- Publicizing opinion poll findings that are more favorable to reform of an institution further encourages support for reform.

A Condensed Chronological History of the US Anti-Death Penalty Movement

This condensed history of the US ADPM is not intended to imply causal relationships between listed events, unless such relationships are stated explicitly. For example, if a sentence referring to a campaign by a state anti-death penalty organization is followed by a sentence about a referendum in that state, the campaign should not be assumed to have substantially influenced the referendum results. Causation is discussed more explicitly in the section on “Strategic Implications.” The current section of the report is not intended to present a comprehensive narrative; it condenses the history into events and processes that have strategic implications for modern social movements. There are slight deviations from chronological order for clarity.

Early History of the ADPM

A small number of pre-modern rulers abolished the death penalty temporarily. Otherwise, the death penalty was a common practice for punishing criminals in most of the world for millennia.[9]

The 1689 English Bill of Rights declared that “cruell and unusuall Punishments” ought not to be inflicted.[10] Tuscany abolished the death penalty in 1786, as did Austria in 1787, except for in cases of revolt against the state.[11] The US Bill of Rights (created 1789), prohibited the infliction of “cruel and unusual punishments” in the Eighth Amendment.[12] Many of the Founding Fathers of the US and early US presidents expressed concerns about the use of the death penalty, seeking to avoid its use if possible. Dr. Rush, one of the signers of the Declaration of Independence, called for the death penalty’s total abolition.[13] Partly as a result of Rush’s advocacy, petitions to abolish the death penalty were introduced in several states in the late 18th century, and several states restricted the death penalty to first degree murder, or murder and treason.[14] Sociologist Herbert Haines claims that, “[a]fter the [American] Revolution, the debate over capital punishment became more visible. Abolitionism was almost indistinguishable from the prison reform movement at this stage. Thus, some of the vocal critics of executions were associated with such groups as the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons.”[15]

In the early to mid-1800s, a religious revival contributed to advocacy against the death penalty in the US. Citizens petitioned state governments to abolish it.[16] In 1814, Ohio became the seventh state to limit capital punishment to those convicted of murder and treason only; the previous six states had done so between 1794 and 1812, a period during which other northern states actually increased the number of capital crimes. However, between the 1820s and the 1850s, several states reduced the number of capital crimes and none increased it; by the time of the Civil War, no northern states had capital punishment for crimes other than murder and treason.[17] Additionally, by 1849, 15 states restricted executions to prison settings, away from public view.[18] This period saw the use of public reports, petitions, speeches, magazines, and various anti-death penalty legislative propositions at the state level. Local advocacy groups were formed, such as the New York State Society for the Abolition of Capital Punishment, and a committee of 30 women in Pennsylvania, whose petition gained nearly 12,000 signatures.[19] It seems that most anti-death penalty advocacy came from educated elites in this period,[20] though in one instance in the late 1840s, 80% of people in a capital case jury pool were dismissed due to their opposition to the death penalty.[21] Several prominent opponents of slavery, including William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, Frederick Douglass, and Horace Greeley, also opposed the death penalty.[22]

In 1846, Michigan banned the death penalty; abolition has been maintained there to the time of writing, despite numerous polls in the late-20th century finding majority support for its reinstatement.[23] Rhode Island (1852) and Wisconsin (1853), also banned the death penalty.[24] Though claiming that “debate in Michigan was no different from that anywhere else,” legal historian Stuart Banner notes that these three states “were relatively egalitarian states in which the conservative Protestant denominations were not very large, and states with populations small enough to permit focused abolitionist groups to have some influence.”[25] Maine also required the governor to pass a separate order to confirm a death sentence, which, according to sociologist Herbert Haines, “had the effect of abolishing executions de facto.”[26] Haines attributes these successes to several factors, including “a general climate of reform in the handling of people on society’s margins.”[27] In addition to these reforms in northern states, all southern states abolished the death penalty for some crimes when they were committed by whites.[28] However, Banner argues that, “[m]uch of the debate that took place in the North simply did not occur in the South because of the perceived need to discipline a captive workforce,” i.e. maintain control of slaves.[29]

Banner summarizes this period as seeing “a consistent string of failures” for the ADPM. “Year after year, in state after state, they had been unable to convince legislatures to repeal the death penalty completely.” For example, in Massachusetts, House committees recommended abolition in 1835, 1836, and 1837, and joint committees of both legislative houses voted in favor of abolition in 1851 and 1854. Nevertheless, abolition was not signed into law there.[30] In New Hampshire, nearly two-thirds of voters rejected a referendum on abolition in 1844.[31] Banner attributes these failures to the lack of focus of anti-death penalty advocacy; advocates often also pushed for wider reform to improve criminals’ wellbeing and for seemingly unrelated issues.[32] However, Bohm argues that, “[b]etween 1800 and 1850, American death penalty abolitionists helped change public sentiment about public executions, especially among many northern-state social elites.”[33]

The Mexican War (1846-8) and the American Civil War (1861-5) seem to have damaged the ADPM, or at least halted some of its work temporarily.[34] Legal scholar Jeffrey L. Kirchmeier summarizes that, “[a]fter the Civil War, the hanging of the conspirators who plotted the murder of President Abraham Lincoln and the widespread use of extra-judicial lynchings by vigilantes made it difficult for anti-death penalty activists to argue that the death penalty was not necessary.”[35] Echoing Banner’s criticism of the ADPM in the first half of the 19th century, Haines argues that the simultaneous focus of the reformers on multiple controversial causes, including capital punishment, prison reform, and antislavery advocacy, may explain why “external events siphoned off much of the momentum and resources that had fueled their efforts against hanging.”[36]

1872-1936: Sporadic, temporary legislative success

The Wilkerson v. Utah (1878) and In Re Kemmler (1890) Supreme Court rulings found death by firing squad and electrocution to not violate the Eighth Amendment.[37] In each case, the convict himself made an appeal against the specific method of execution, rather than against capital punishment as an institution.[38]

In 1887, Maine permanently abolished the death penalty, having previously abolished then reinstated it. Both Iowa (abolished 1872, reinstated 1878) and Colorado (abolished 1897, reinstated 1901) temporarily abolished the death penalty. The short-term effects of well-publicized crimes and executions may have encouraged these legislative changes.[39] In 1889, a Minnesota law required that executions take place before sunrise and prohibited newspapers from reporting details of the executions[40]; the United Kingdom had already stopped carrying our executions in public by this point.[41] Opposition to capital punishment in Minnesota had reflected objections to the execution of a “woman or girl,” moral objections to state-sanctioned killing, views on the ineffectiveness of capital punishment as a deterrent, and practical arguments about the quality of jurors.[42] Minnesota had temporarily introduced a de facto moratorium on executions from 1868-85.[43] The primary motivation for the 1889 law seems to have been to reduce the perceived corrupting and degrading influences on society of public executions.[44] Explicit abolition legislation was passed in the House of Representatives in Minnesota in 1893, but this was rejected by a Senate committee. Several subsequent bills failed.[45]

From the late 19th century until the mid-20th century, many states replaced hanging with the electric chair or gas chamber as their principal methods of execution,[46] apparently due to concerns about the suffering of the executed criminals.[47]

Haines characterizes anti-death penalty activism at the turn of the century as “based primarily at the state and local level”; several local groups were formed, such as The Anti-Death Penalty League in Massachusetts in 1897.[48] Opposition came “not so much from religious leaders, as it had in the nineteenth century, but from judges, prosecutors, and the police.”[49]

As Kirchmeier summarizes, in the early 20th century, a period known as the Progressive Era, “social reformers were concerned about government corruption and focused on areas such as poverty, housing, social injustice, corruption, and crime. The main battleground for reforms were fought at the state level.”[50] In 1911, legislation finally successfully abolished the death penalty in Minnesota.[51] It has never been reinstated, although there were bills to restore the death penalty there each year for 14 years.[52]

Eight other states abolished the death penalty entirely in the late 19th and early 20th centuries but subsequently reversed the change.[53] Many other states came close to abolition.[54] Several long-term factors probably help explain why some states abolished the death penalty during this period while others did not, including the size of the non-white populations[55] and a longer-term lack of support for abolition in Kansas, Minnesota, and North Dakota.[56]

The newspaper accounts cited by sociologists John F. Galliher, Gregory Ray, and Brent Cook (1992) show several frequent features of the abolition efforts at this time. State governors seem to have taken an active, independent role in abolishing the death penalty in several states, including Kansas, Washington, Oregon, Arizona, and Colorado. In two states, the governor was the president of a local anti-death penalty organization. Only in Tennessee does there seem to have been active opposition by the governor. In Colorado and Minnesota, the newspapers themselves seem to have been advocates of abolition or provided unfavorable coverage of executions. Prison officials advocated abolition in Washington and Oregon, seemingly before governors or legislators took action, though some officials opposed abolition in Tennessee.[57] In Oregon and Arizona, abolition was introduced through referendums with very narrow margins, with votes that were split 100,552-100,395 and 18,936-18,784, respectively.[58] A newspaper headline from Tennessee claimed that the legislature had passed the abolition bill there only after “vigorous debate.” However, South Dakota passed a bill by 63 votes to 24 and North Dakota’s bill abolishing the death penalty for murder passed the House of Representatives unanimously. Arguments used by the ADPM at this time included the “barbarism” of capital punishment and its ineffectiveness as a deterrent.[59]

Factors encouraging the reinstatement of the death penalty in some states after the Progressive Era were the economic downturn that followed the prosperity of the early 20th century, the occurrence of notable crimes or an overall increase in the crime rate, the occurrence of lynchings in response to these crimes, panic about the threat of revolution, and the claims in four states of individual murderers that they would not have committed their crimes if the death penalty had existed.[60] By comparison, officials in Minnesota responded harshly to lynchings, which may have helped to maintain abolition there.[61] Reinstatement occurred through a referendum in Arizona, with a much wider majority than the referendum that had led to abolition. Elsewhere, reinstatement was supported by legislators, newspapers, and in Oregon, the state Bar Association.[62] Some people in Colorado, Arizona, and Tennessee seem to have been indifferent to abolition when it was first proposed, and the legislation seems to have been viewed as an experiment; when abolition seemed to cause adverse effects (that is, increased lynching or crime), reversal came within a few years.[63]

The total number of executions in the US declined from 161 in 1912 and 133 in 1913 down to 99 in 1914 and 65 in 1919, which was the lowest ever number of executions per capita on record to date. This decline was temporary, however; the total rose back to “the 140s” by 1921 and peaked at 199 in 1935.[64]

In 1925, the American League to Abolish Capital Punishment (ALACP) was founded. Its executive committee comprised three prison wardens, a psychiatrist, and three academics. The ALACP distributed articles and pamphlets, and its leaders gave speeches. The ALACP provided support for legislative campaigns for abolition in “at least 11 states, providing testimony and mailing tens of thousands of pieces of literature a year.” It also established a committee to research deterrence and racial discrimination in capital sentencing. The ADPM’s legislative efforts failed between the 1920s and 1940s, however.[65] Activism similar to the ALACP’s was developing in the UK at this time.[66] At the same time as the ALACP’s activism, celebrities like Henry Ford publicized their opposition to the death penalty,[67] as did some prison officials.[68]

In 1936, the last US public execution took place — 68 years after the last in the United Kingdom.[69]

1936-1966: Declining execution rates

From the late 1930s, a sharp decline in rates of executions began. This continued until the late 1960s, when no executions were taking place.[70] Though the fall in executions began initially in northern states such as Illinois and New Jersey,[71] the change was sharpest in the South, where the death penalty had been used most frequently.[72]

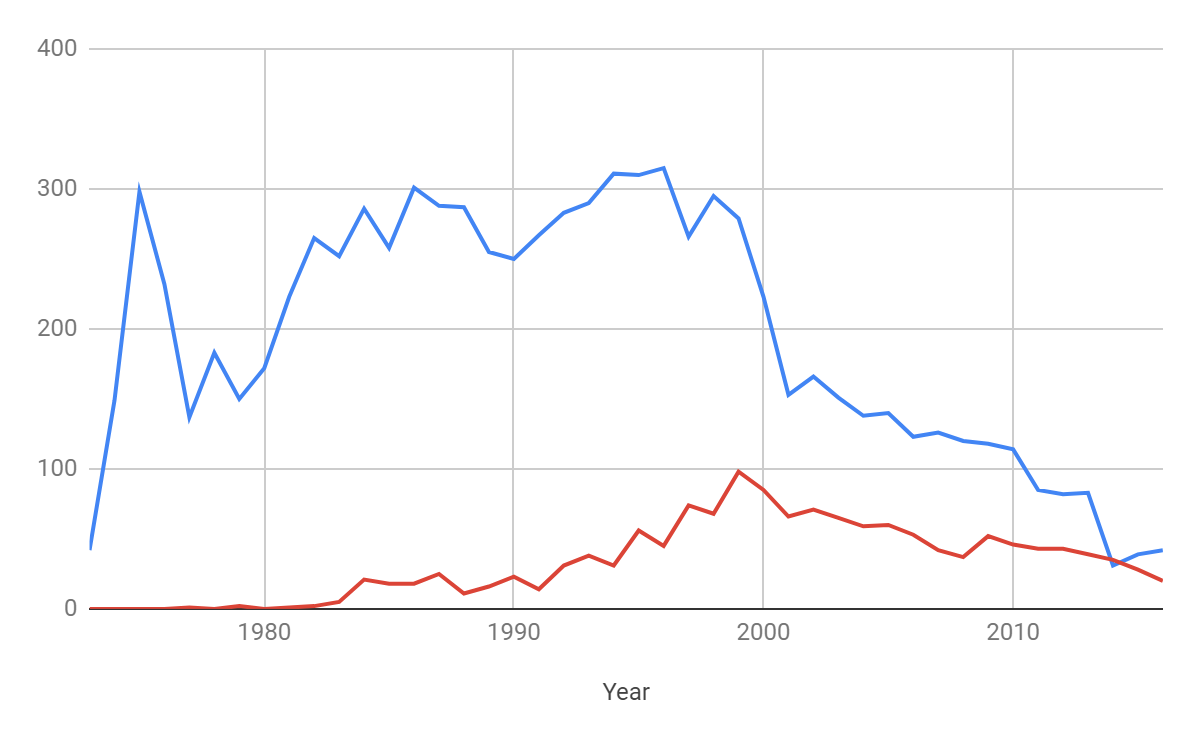

Figure 1: Number of executions per year, 1931-2019.[73]

Trends that began in the 19th century or early 20th century that may have encouraged the beginnings of this decline include:

- The development from the late 19th century onwards of scientific and social scientific theories that crime was caused by heredity and environmental factors, rather than chosen freely by the criminal.[74]

- Increased awareness of executions that were controversial due to the youth or possible innocence of the executed, or due to concerns about racial motivations.[75]

- The increase in empirical evidence that challenged the claim that the death penalty was a more effective deterrent than its alternatives.[76]

- The decline in the early- to mid-twentieth century of income inequality,[77] which is correlated with death penalty support.[78]

More substantial factors that seem likely to have contributed to the decline in executions include:

- The growing international trend towards abolition.[79]

- Declines in the use of mandatory death sentences and the number of capital offenses[80] as well as increasing restrictions on the use of the death penalty at the state level.[81]

- The growing number of newspapers and religious organizations that were publicly criticizing the death penalty,[82] as well as advocacy from the ALACP and others.[83] Due partly to these factors, the attitudes of juries (and hence the public) may have been changing, with juries becoming less willing to impose death sentences.[84] Another trend that suggests that there was increasing concern about the death penalty in the first half of the 20th century is the increasing time delays between the imposition of death sentences and the execution of the convict.[85] From the mid-1950s, Gallup poll results show decreasing public support for capital punishment.[86] Execution rates in France also seem to have declined as public support declined there.[87]

- The “criminal procedure revolution” implemented by Chief Justice Warren’s Supreme Court, from 1961 onwards, sparked by the Mapp v. Ohio ruling. Though not focused specifically on the death penalty, these procedural changes presented death row inmates with the opportunity to litigate and postpone their executions.[88] Banner notes that, by the 1960s, “the annual number of death sentences regularly exceeded the number of executions by a hundred or more… Clearly events after sentencing were more important than sentencing itself in causing the execution rate to decline.”[89] Commutation of sentences seems to have already declined by the 1960s, so Banner attributes the continued drop in executions after this point to the much increased number of appeals to higher courts from condemned criminals.[90] Legal scholars Carol S. Steiker and Jordan M. Steiker argue, however, that in the long term, these procedural changes may have encouraged a public perception and narrative that criminal procedure was over-regulated, increasing resistance to more substantial reforms to ensure better protections for criminals.[91]

- The increased support and mobilization for movements that advocated some form of expansion of the moral circle in the 1950s and 1960s, such as those addressing civil rights and poverty.[92] Herbert Haines speculates that the death penalty continued to decline in the post-war period because, “as practiced, many people found it to be glaringly inconsistent with the ascendant ideas of the times,” which included wider mass social movement participation and momentum for civil rights.[93] Some advocates explicitly connected civil rights and death penalty issues.[94]

- Haines summarizes that, “Philip Mackey speculates that the lingering shock of the Holocaust may have been partly responsible” for continued decline.[95]

- According to Banner, “[t]he murder rate had dropped slightly, but not enough to make this big a difference” to the execution rate.[96]

- From the late 1960s, litigators were systematically challenging the use of the death penalty.[97]

Internationally, interest in abolition of the death penalty seems to have grown in the wake of the Second World War, partly in relation to an increased interest in enforcing human rights more broadly.[98] Eleanor Roosevelt may have sought to remove references to the death penalty in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was adopted in by the UN in 1948. Roosevelt noted in the drafting committee that there was a “movement underway in some states to wipe out the death penalty completely.”[99]

In 1948, Caryl Chessman was sentenced to death for kidnapping with bodily harm. In the following years, he launched several appeals, acting as his own attorney, and wrote several books. His case brought international appeals for mercy from well-known figures such as Alduous Huxley.[100] Haines notes that when Chessman was put to death, “angry mobs attacked US embassies in several countries.”[101] The sentencing to death of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who spied for the USSR, in 1950, also provoked international protests.[102] Barbara Graham claimed to be innocent but was executed in 1955; a book and Hollywood film were made about the case.[103]

In the 1950s and 1960s, there seems to have been an increased focus on reform of the criminal system among the educated elite in both Europe and the US, including on restriction or abolition of the death penalty in some European countries.[104] In the same two decades, US religious organizations representing both mainline and evangelical Protestantism put out official statements criticizing capital punishment.[105] Intellectuals including Albert Camus and Arthur Koestler added to this criticism, as did politicians, including the governor of Ohio.[106]

From 1950, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Legal Defense Fund (hereafter LDF) defended African Americans in several capital punishment cases. The LDF was a growing, well-resourced group[107] that had contributed to favorable decisions in landmark Supreme Court rulings on African American civil rights, such as Brown v. Board of Education (1954).[108]

From the 1950s, conservative governors and law enforcement officials in the South began to frame civil rights activism as “criminal” and challenging “law and order,” calling for the arrest of activists who were portrayed as “street mobs” and “lawbreakers.”[109]

In 1953, the Royal Commission on Capital Punishment noted that the death penalty was used for few crimes in the UK and that, “the real issue is now whether capital punishment should be retained or abolished.” Haines believes that this encouraged abolition efforts in both the UK (which abolished the death penalty in 1969) and the US.[110] Reform efforts and proposals for a moratorium in the UK also seem to have encouraged Canada[111] and New Zealand’s[112] ADPMs.

New state-level abolitionist organizations were formed in the late 1950s, some of which were tied to the ALACP.[113]

In 1957, Hawaii banned the death penalty; it was the first state to do so since 1916.[114] Alaska (1957), West Virginia (1965), and Iowa (1965) also subsequently banned the death penalty.[115] In 1963, Michigan, which had abolished capital punishment for all crimes except treason through legislation in 1846, amended its constitution to prevent subsequent legislation from reintroducing capital punishment and to formally abolish capital punishment for treason.[116] Though they subsequently reintroduced it, Delaware (banned 1958, reinstated 1961),[117] Oregon (banned 1964, reinstated 1978),[118] and New York (banned 1969, reinstated de jure but not de facto in 1995)[119] also banned the death penalty in this period, in Oregon’s case through a referendum with 60% of the vote.[120] Kirchmeier summarizes that public opinion in Oregon had been influenced by “a governor who was outspoken against the death penalty, a large political and public campaign (including ads by celebrities) against the death penalty, and public attention on a sympathetic condemned female inmate.”[121] Vermont (1965) and New Mexico (1969) also introduced partial bans.[122] Many other states considered legislation at this time.[123]

In 1958, two public opinion polls in France found only 39% and 33% support for capital punishment, compared to 50% and 58% opposition. However, after two convicts undergoing life imprisonment murdered a warder and a nurse in their prison, a poll in 1972 found 53% support compared to 39% opposition. President George Pompidou had earlier reprieved six prisoners but did not reprieve these two men, who were executed that year.[124]

In 1962, the American Law Institute (ALI) created its Model Penal Code, which contained recommendations for rationalizing capital punishment administration at the state level; the recommendations contrasted with contemporary state practice but did not advocate abolition.[125]

In 1964, the book The Death Penalty in America by Hugo Adam Bedau, a committed anti-death penalty advocate, was published.[126] In 1965, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) issued a statement against the death penalty.[127] That same year, Attorney General Ramsey Clark wrote a letter to Congress saying that the Department of Justice favored the abolition of the death penalty[128]; he appears to have opposed the death penalty for both moral and practical reasons.[129]

In 1965, Vermont and New York limited the death penalty to fewer crimes.[130]

1966-72: Litigation and temporary legal success through Furman v. Georgia

In 1961, two law review articles suggested that litigators might be able to show the death penalty to be inconsistent with contemporary standards of decency,[131] which would conflict with the Eighth Amendment, as interpreted by Chief Justice Earl Warren in the 1958 Supreme Court Trop v. Dulles ruling.[132] In a dissenting opinion on the 1963 Rudolph v. Alabama case, three Supreme Court Justices suggested that the Court could be willing to hear arguments against the death penalty in future cases.[133] Justice Goldberg had previously circulated a memorandum against capital punishment to the rest of the Supreme Court; on the request of Justice Warren, he did not publish it. However, in an interview, Goldberg’s clerk said that he “sent copies of the dissenting opinion to every lawyer in America who [he] knew.”[134]

Presumably encouraged by these signals of the death penalty’s legal vulnerability, the LDF began a litigation campaign in 1966 to force a moratorium on capital punishment.[135] Although initially intending to focus on African Americans convicted of rape, their involvement subsequently grew to encompass all those given a death sentence, regardless of race. Legal scholar Eric L. Muller explains this shift as having been a result of the campaigning and legal logic of the LDF combined with a sense of ethical duty to protect all convicts equally, without discrimination by race.[136] Kirchmeier summarizes the LDF’s three tactics as, “(1) challenging cases in the Supreme Court; (2) developing and using social science evidence in the courts; and (3) attempting to block all executions while the litigation was in progress. The LDF’s goal of achieving a judicial moratorium involved a nationwide effort to enlist and work with lawyers in various states.”[137] The LDF argued that “death is different” and that, consequently, juries needed to be given precise standards on when to pass sentence.[138] In 1967, the ACLU joined the LDF in its litigation campaign.[139] A few leading death penalty abolitionists did provide information to the LDF and ACLU,[140] but both of these groups were predominantly civil rights groups that diverted resources from their other campaigns.[141]

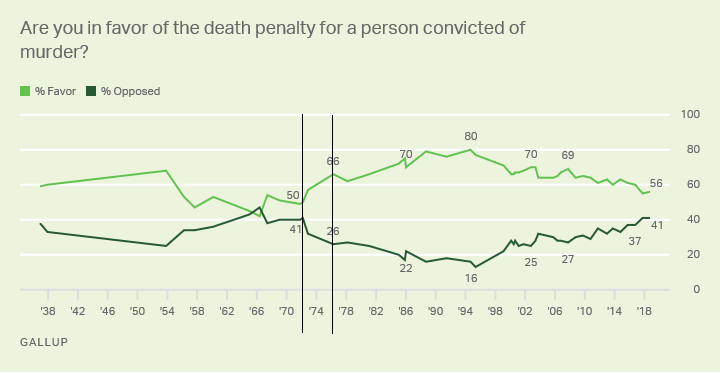

Nineteen sixty-six was the only year in which Gallup polls found that a higher percentage (47%) of the US public were opposed to the death penalty for murder than supported it (42%). In 1967, support rose back up to 54% but then sunk back down to 51% and 49% in 1969 and 1971, respectively.[142] The temporary spike in support in 1967 may have been caused by, “extensive publicity surrounding the convictions of Albert DeSalvo (a.k.a. ‘the Boston Strangler’) and Richard Speck (who had murdered eight student nurses in Chicago) just before polling began.”[143] Crime rates were also rising,[144] which seems likely to have encouraged public support for the death penalty.[145] Crime was also an important political issue; Richard Nixon used a “law and order” campaign in the 1968 election.[146] Nevertheless, Gallup polls showed lower support for capital punishment in 1956-72 than any polls since 1972 have done.[147]

A committee for the US Senate seems to have considered federal abolition legislation, though the bill never progressed beyond the committee stage.[148]

From 1968 to 1977, no executions were carried out.[149] State politicians and attorneys general were increasingly speaking out against the death penalty, including the governor of Arkansas commuting the sentences of all 15 individuals on death row in the state.[150] In 1968, Attorney General Ramsey Clark asked Congress to abolish the federal death penalty.[151] Haines summarizes that, “[b]y 1971, nine states had abolished the death penalty, four more had no one on death row, and anti-death penalty bills had reached the floor of state legislatures in California and Massachusetts, as well as the U.S. House of Representatives.”[152]

In 1968, the Supreme Court rulings of United States v. Jackson and Witherspoon v. Illinois regulated capital trials; the former ensured that judges rather than juries retained the right to impose death sentences, and the latter limited the state’s ability to exclude conscientious objectors to the death penalty from juries.[153] In 1970, the Fourth Circuit court ruled in Ralph v. Warden that the death penalty for rape violated the Eighth Amendment if lives were not endangered.[154] However, in 1971, the Supreme Court ruled in McGautha v. California that the lack of “definitive standards” for the use of the death penalty did not violate the Constitution.[155]

There were 13 votes on whether to reintroduce capital punishment held in the UK’s Parliament between 1969 (the year of abolition) and 1994, but all were defeated. Shortly before abolition there, a 1969 poll found that 85% of respondents were in favor of retaining the death penalty. Legislators in Germany had also proposed the reinstatement of the death penalty in the 1950s and 1960s but had failed, despite majority public support.[156]

By the end of 1970, the number of convicts on death row in the US had risen to over 600, up from 435 in 1967, due at least in part to the LDF’s litigation to prevent their execution.[157]

On February 17, 1972, the California Supreme Court ruled in The People of the State of California v. Robert Page Anderson that the death penalty violated Section 6 of the California Constitution, which stated that “cruel or unusual punishments” should not be inflicted. The justices considered whether the punishment was proportionate or excessive (i.e. “unusual”) and whether capital punishment was cruel by “contemporary standards” or not. There was also some consideration of whether vengeance was a suitable justification for punishment and whether capital punishment was an effective deterrent.[158] National Gallup polls conducted in October 29 to November 2, 1971 and March 3 to March 5, 1972 found that 49% and 50%, respectively, of the US supported the death penalty for a person convicted of murder.[159] This suggests that the Anderson decision either slightly increased public national support for capital punishment or had no effect.[160]

Though Congress had passed two death penalty statutes in 1971,[161] the House Judiciary Committee considered proposals for a two-year moratorium on federal executions in 1972, as well as proposals for abolition.[162] The chairman explicitly highlighted that, “[t]he importance of the measures under consideration [lay] in the fact that the U.S. Supreme Court” was considering the constitutionality of the death penalty.[163] In the absence of information about the subsequent fate of these bills,[164] it seems likely that they were dropped at the committee stage.

On June 29, 1972, the US Supreme Court ruled in Furman v. Georgia (hereafter, Furman) that the carrying out of the death penalty for two convicts in Georgia constituted “cruel and unusual punishment in violation of the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments.” However, the judgement was made by a slim five-to-four majority, and all of the justices submitted separate opinions, having been unable to agree on a rationale for the decision.[165] Two justices concluded that the death penalty was always “cruel and unusual,” but three concluded that the death penalty was only cruel and unusual as practiced at the time, with arbitrary sentencing.[166] In previous years, the LDF and other lawyers challenging the death penalty had focused on the arbitrariness of death sentencing,[167] so these litigation efforts seem likely to have been influential in the decision.[168] The decision may also have been influenced by trends in judicial activism, the standardization of criminal procedure, the Court’s efforts to minimize the effects of racism, and changes in public opinion.[169] The effect of the ruling was to nullify most capital punishment laws that existed at the time in the country.[170] Before,[171] during,[172] and shortly after[173] the Furman case, various involved actors and external commentators predicted the imminent abolition of capital punishment.

1972-86: Backlash, legal reversal through Gregg v. Georgia, and the ADPM’s initial shift towards public-facing advocacy

There is anecdotal evidence of outrage at the Furman decision among politicians and officials.[174] Legal scholar Corinna Barrett Lain notes that, “[w]ithin a day of the decision, legislators in five states had announced their intent to enact new death penalty legislation and seventeen congressmen had joined in sponsoring a constitutional amendment to reinstate the death penalty.”[175] In 1972 and 1973, The New York Times’ coverage of the death penalty was unusually frequent (around 120 and 90 articles respectively compared to around 40 and 25 in the two previous years) and unusually supportive of the death penalty (around 5 and 35 more supportive than hostile articles compared to roughly even coverage in the previous two years).[176] These changes do not seem to have occurred to the same extent in magazine coverage.[177]

On November 7, 1972, California reintroduced the death penalty, overturning the People v. Anderson decision from earlier that year. This was achieved with 67.5% support through the Proposition 17 ballot initiative.[178] The Furman ruling seems to have led to some complacency among activists, funders, and politicians who otherwise might have been more determined in their efforts to defeat the California ballot initiative.[179]

Gallup polls conducted on March 3-5, 1972 and November 10-13, 1972 (shortly before and after the Furman ruling) show an increase from 50% to 57% support for the death penalty for a person convicted of murder.[180] From this point public support for the death penalty continued to rise until 1994, when it peaked at 80%.[181]

The influence of rising crime rates on this trend is unclear. Mismatches in the chronology of changes in these two variables suggest that the increasing crime rate was not the only cause of changing public opinion.[182] The small rises in self-reported fear of crime in this period suggest that increased crime rates are unlikely to have caused an increase in the public’s support for punitive treatment of convicts.[183] A paper by Timothy R. Johnson and Andrew D. Martin compares public opinion data from the General Social Survey before and after three key capital punishment cases; there is a significant difference in aggregate public opinion after the Furman ruling but not after the other two rulings.[184] Another paper models the determinants of support for the death penalty; though it controls for seven other factors, all four models find that the dummy variable for the period between the Furman ruling and the 1976 Gregg v. Georgia ruling (which clarified that the death penalty could comply with the Constitution[185]) is significant, suggesting that Furman increased support for the death penalty. However, this paper also found that the murder rate and income inequality (which also began to rise at around this time[186]) were significantly associated with public support for the death penalty and with the number of executions.[187]

At least one scholar has concluded that increasing violent crime rates were the most important factor in driving increases in support for capital punishment,[188] and there is evidence of increasingly punitive attitudes towards criminals more generally at this time.[189] It also seems plausible that the increase in pro-death penalty legislation in the period after Furman (see below) contributed to a social norm of high support for the death penalty.

Figure 2: Public opinion on the death penalty, as measured by Gallup polls, 1937-2018,[190] with lines to mark on the dates of the Furman v. Georgia (1972) and Gregg v. Georgia (1976) rulings.

In December, 1972, Florida signed new legislation restoring the death penalty there.[191] Ninety-seven percent of the National Association of Attorneys General voted in favor of asking Congress and the state legislatures to introduce new death penalty legislation.[192] By 1976, 35 states and the federal government had redrafted laws to enable the use of capital punishment in a manner that complied with the Furman ruling.[193] New Mexico, having abolished capital punishment in 1969, reinstated it in 1973.[194] Oregon and Michigan, both of which had banned capital punishment (in Michigan’s case, 127 years previously) sought to maintain their authority to use the death penalty, though their bills failed.[195] After 121 years of near abolition, Rhode Island’s legislature passed a capital punishment law in 1973 for prisoners who committed murder.[196] Nevertheless, the legislative backlash seems to have occurred mostly in states that had used capital punishment frequently before Furman.[197] One strategy to remove arbitrariness and comply with Furman was to make capital punishment mandatory for some crimes. This practice was very rare until Furman, only having been in use in Massachusetts for combined rape and murder and in Rhode Island and New York for murder while in prison.[198] Sixteen states enacted mandatory death penalty laws after Furman.[199]

Figure 3: Death sentences (blue) and executions (red) per year, 1973-2016.[200]

Resistance to Furman was especially strong in the South, including among politicians and law enforcement officers.[201] Opponents of Furman may have learned from the experience of the Brown v. Board of Education (1954) desegregation ruling that resistance to implementation, including via litigation and redrafted legislation, could prevent a legal ruling from having practical effect, at least temporarily.[202]

Scholars and pundits describe the 1960s and 1970s as the period when the Republican Party used a “Southern Strategy” to win votes from southern white voters by indirectly appealing to racism.[203] Criminal justice issues were an important part of this indirect discrimination, given racial disparities in crime and punishment,[204] and given that “law-and-order” politics were posed as an alternative to illegal civil rights direct action, as in 1968 Republican presidential candidate Richard Nixon’s television advert campaign that promised to defend “decent citizens” from street crime and civil rights protests.[205] Recent survey evidence suggests that racial prejudice affects attitudes towards capital punishment,[206] so it seems plausible that the messaging and mobilization of the Southern Strategy encouraged support for the death penalty. This may have been especially so in the South, where resistance to Furman was the strongest.[207]

By the early 1990s, there was a common, yet minority, perception that racial prejudice motivated the law-and-order agenda of politicians; a Gallup poll found that over half of surveyed African Americans and one-third of surveyed whites believed this.[208] The Supreme Court’s recent changes to criminal procedures[209] may also have made the ruling more vulnerable to backlash from those who sought harsh policies for criminals.[210] By comparison, rising crime rates in the UK in the 1950s do not seem to have been mobilized for a pro-death penalty or tough-on-crime political position,[211] and political polarization on capital punishment may have decreased there at that time.[212]

In the face of the backlash among legislators and the public, the LDF sought better empirical research to encourage continued judicial restrictions on capital punishment.[213] After discussion with the LDF, the ACLU agreed to take responsibility for the legislative efforts of the ADPM, but until 1978, the directors of the ACLU’s Capital Punishment Project (CPP) were volunteers. At the state level, ACLU affiliates were involved in legislative campaigns in California, Kansas, New Jersey, and Vermont, using tactics including letter-writing and telephone campaigns, community meetings, and lobbying. However, one of the CPP directors wrote in a letter to ACLU leadership that, “[b]ecause the death penalty project is not as current as ‘Privacy’ or as dramatic as ‘Rights of Children,’ the smaller overworked affiliates are forced to make decisions and many of our project’s activities have lost-out.” They added that many members felt “that this is one project that can slide until the issue is before the Supreme Court again.”[214]

The North Dakota legislature had already abolished the death penalty in 1915 for all crimes except treason and murder committed by an inmate already serving a life sentence. These last remaining capital crimes were removed in 1973.[215]

In 1975, the Washington state legislature abolished the death penalty, though new mandatory death sentencing laws were reinstated in the same year through Initiative 316,[216] which had 69% public approval.[217] The new law was found unconstitutional by the Washington Supreme Court, though the legislature introduced a law to comply with constitutional requirements in 1981.[218]

In 1976, after a period of systematically commuting all death sentences, the Canadian Parliament abolished death sentences. In 1987, a bill to move towards restoring capital punishment was rejected despite majority public support for the practice.[219]

In 1976, the US Supreme Court considered five cases, collectively abbreviated as Gregg v. Georgia (hereafter, Gregg), where the defendants sought a ruling that the death penalty was always “cruel and unusual.” On July 2 of that year, the court upheld the death penalty in these cases by seven-to-two, defining “cruel” punishment as punishment that is “so totally without penological justification that it results in the gratuitous infliction of suffering.”[220] The judgement noted that the concerns of arbitrary imposition expressed previously in Furman could be addressed through “carefully drafted statute,” which would mean that the death penalty could then be applied in a constitutionally acceptable manner. The passage of state legislation in response to People v. Anderson (California’s ruling against the death penalty) and Furman (the federal Supreme Court's ruling against the death penalty) seems to have been important in the decision.[221] On the accusation that the death penalty was an ineffective deterrent, the Supreme Court concluded that, “there is no convincing empirical evidence either supporting or refuting this view.”[222] Two Supreme Court judgements issued on the same day as the Gregg ruling clarified that capital punishment could be constitutional but that mandatory capital punishment could not.[223]

Following these judgements, Gallup polls found a temporary decrease in support for the death penalty for murder, falling from 66% support in April 1976 to 62% support in March 1978.[224] However, a paper by Timothy R. Johnson and Andrew D. Martin found no significant difference in public support before and after the Gregg decision, as measured through the General Social Survey.[225]

In 1976 and 1977, The New York Times’ coverage of the death penalty was unusually frequent (around 180 and 190 articles compared to around 50 in the previous year) and very slightly more critical of the death penalty than in surrounding years.[226] These changes in the New York Times’ coverage were not matched closely by magazine coverage of the death penalty, however.[227]

From 1976-82, five of the six executed convicts were white, and four of the six chose not to appeal their death sentences. These two unusual features of the first few executions after Gregg may have allayed concerns about the return of capital punishment.[228] Nevertheless, Gregg seems to have sparked resistance from the ADPM. The National Coalition Against the Death Penalty (NCADP, later renamed the National Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty) was formed in 1976. The NCADP brought credibility to the ADPM from its professional and religious affiliate organizations, pressured governors to veto death penalty bills, and encouraged grassroots mobilization via the clergy but had limited funding and influence until the mid-1980s.[229] The group Southern Coalition on Jails and Prisons organized protests against the death penalty on Christmas Eve 1976, and on the weekend after the first post-Gregg execution (of Gary Gilmore in 1977) outside prisons, statehouses, and governors’ mansions. During Easter 1977, the group gathered between 1,000 and 3,000 protestors at the Atlanta state capitol. The group had Christian origins, and the protests were vigils with prayers.[230]

Similar protests and vigils continued through the 1970s. Haines notes that until the mid-1980s, “abolitionists refused to let a convict be put to death without their being there to bear witness,” though they were “often outnumbered by boisterous pro-death penalty demonstrators on hand to celebrate the imminent demise of a convicted murderer.”[231] Some activists also held direct action sit-ins against governmental targets and used publicity stunts such as dumping fake execution victims on a public building’s steps and performing street theater.[232] Despite some internal disagreement, Amnesty International USA (AIUSA) also adopted an increased focus on the death penalty, holding a major news conference at the UN headquarters in New York in 1979 and having 100 local groups with death penalty coordinators by June 1980.[233] Amnesty International had been formed in 1961; it had initially focused on securing the release of political prisoners through letter-writing and pressuring law enforcement agencies and governments but had already become active in the European ADPM.[234] Haines characterizes public-facing “political abolitionism” in the late 1970s and early 1980s as “weak and ill formed”; the movement remained “lawyer-dominated.”[235]

A working paper by undergraduate student Marnie Lowe “coded instances of published [anti-death penalty] movement speech in The New York Times and Los Angeles Times for the frames they feature… from 1965 to 2014.” By Lowe’s categorization, the second chronological era analyzed, 1976-85, saw an increase in the use of “moral” (as opposed to “instrumental”) arguments by legal advocates as the primary frame quoted in newspaper articles. The rise was to 75%, up from 41% in the 1965-75 era; use by activists and anti-death penalty movement sympathizers remained similar. In contrast, by 1993, legal advocates had ceased to use moral framings entirely. In Lowe’s categorization, focus on discrimination, arbitrariness, innocence, and errors are classified as “instrumental,” rather than “moral” framings.[236]

From 1977 to 1999, most executions occurred in the South, which may have been due to the higher homicide rates and to differences in how states provided defense lawyers,[237] as well as longer-term cultural and political factors.[238]

In 1977, the Coker v. Georgia Supreme Court ruling found that imposing the death penalty for the rape of an adult woman was a “grossly disproportionate and excessive punishment.”[239] From 1977 onwards, various other Supreme Court rulings restricted the types of cases for which capital punishment was eligible for use.[240] For example, Godfrey v. Georgia (1980) prohibited death sentences based on vaguely defined aggravating circumstances,[241] Ford v. Wainwright (1986) prohibited the use of capital punishment on the insane,[242] and Thompson v. Oklahoma (1988) prohibited execution of those aged fifteen or younger.[243]

Having voted against the death penalty in 1914 and 1964, the people of Oregon voted to reinstate it in November 1978 and in 1984 (after the 1978 law was declared unconstitutional) through referenda.[244] In 1979, the Supreme Court of Rhode Island declared that the capital punishment law that had been introduced in the state after Furman constituted cruel and unusual punishment.[245] No one was ever executed under the post-Furman law. Indeed, no one has been executed in the state since 1845, and in 1984, the legislature removed the death penalty from the state’s penal code.[246]

From 1982 onwards, several studies began to show that capital punishment was more expensive than alternatives.[247] Until the results of such studies became widely known, pro-death penalty advocates seem to have used cost arguments to their advantage.[248]

In 1983, the Supreme Court ceased consistently ruling in favor of criminals sentenced to death. From 1976-83, the Court had ruled in favor of 14 of the 15 appeals for death-sentenced criminals that had been fully argued in the Court. In 1983-4, however, the Court allowed a variety of loosenings of the restrictions on capital punishment, such as seeming to permit inconsistent application of the death penalty in Pulley v. Harris (1984).[249] In 1983 and 1984, The New York Times’ coverage of the death penalty may have been unusually frequent relative to the years that directly preceded and followed.[250]

In 1983, the Council of Europe (CoE) added Protocol No. 6 to the European Convention on Human Rights, which abolished the death penalty, except “in respect of acts committed in time of war or of imminent threat of war.”[251]

In the same year, the first of many innocence projects — university groups led by attorneys and professors of law or journalism that made use of student volunteers to expose errors in death sentencing — was set up in Princeton, New Jersey. By 2006 the group, Centurion Ministries, had helped to exonerate 14 convicts, predominantly from life sentences or death sentences.[252]

Massachusetts abolished capital punishment in 1984. Abolition was driven by a Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court decision in spite of the Gregg decision and an amendment to the state’s constitution approved by voters two years before that noted, “[n]o provision of the Constitution, however, shall be construed as prohibiting the imposition of the punishment of death.”[253] Previous political efforts had led to the passage in 1951 of a sentencing law that allowed juries to recommend that life imprisonment be imposed instead of the death penalty, but abolition legislation had failed on multiple occasions, despite anti-death penalty lobbying and the report of a state-appointed commission which had encouraged abolition. The state’s voters had also rejected abolition in a referendum in 1968.[254] A pro-death penalty Republican governor failed to push death penalty bills through the state legislature in 1994 and 1995, so he attempted to introduce similar proposals through a ballot initiative. However, the specifics of the Massachusetts Constitution prevented the use of ballot initiatives to reinstate capital punishment.[255] In 1998, state legislators rejected reinstatement legislation by a single vote[256] despite a poll the previous year finding 74% public support for the death penalty for those who murdered a child.[257] Anti-death penalty advocacy by the Pope and by Massachusetts Catholic bishops helped to encourage legislators to reject death penalty legislation again in 1999.[258]

From the mid-1980s, the number of annual exonerations from death row seems to have begun to gradually increase, albeit with high variation between years: Between 1973 and 1985, there were between zero and four exonerations per year (mean 1.8), which increased to between one and thirteen in 1994-2006 (mean 5.3). By March 2007, the cumulative total of exonerations since 1973 was 123.[259]

1986-97: Peak support for the death penalty, some setbacks, some successes, and the beginnings of the ADPM’s shift towards messages and asks with broader appeal

Kirchmeier summarizes that in 1986, “Chief Justice Rose Bird and two other California Supreme Court justices were voted off the bench following a political campaign that focused on their votes on reversing death sentences.” Similarly, “in a 1996 retention election, Tennessee Supreme Court Justice Penny J. White was voted off the bench after a number of groups campaigned against her because of one decision in which she voted for a new death sentencing hearing for a defendant.”[260] These examples may be indicative of a wider trend of public support for the death penalty encouraging a more pro-death penalty attitude among elected judges. Looking at state Supreme Courts, political scientists Paul Brace and Brent D. Boyea (2008) found that public opinion has no direct effect on the likelihood that the Courts reverse a capital punishment ruling unless the justices are directly elected; if the justices are elected, the level of public support for the death penalty has nearly twice as much of an effect as the justices’ own political ideology.[261]

In 1986, the Ford v. Wainwright Supreme Court ruling prevented the use of capital punishment on the “insane.”[262] In the same year, the American Bar Association set up its Death Penalty Representation Project.[263]

According to Lowe’s content analysis of The New York Times and Los Angeles Times articles, 1986-1992 saw a downward shift in the use of “categorically wrong” arguments as the primary frame of the ADPM’s quoted or written statements to 27% from 43%. During the same period, there was a temporary increase in “wrong at the edges” framing (up to 13% from 3%) and other moral frames (3%). The years 1986-92 saw the use of moral framings drop substantially by activists (down to 28% from 42%) and legal advocates (down to 60% from 73%); the overall use of moral framings was sustained by an increase in use by movement “sympathizers,” Lowe’s category for individuals who “lack official affiliation with movement groups but affirmatively oppose the death penalty.”[264]

In 1986, Charles Fulwood, the new director of Amnesty International USA’s (AIUSA) death penalty program, conducted a survey to explore aspects of the death penalty that were most unpopular in Florida. Fulwood’s aim was to exploit these concerns to gradually reduce the popularity of the death penalty through targeted messaging.[265] The survey found that fewer than half of respondents supported the execution of convicts under 18, people guilty of unpremeditated murders of family members or friends, people with histories of mental illness, or the intellectually disabled. Fulwood stated in a 1992 interview that he decided to “focus on doubt, rather than feeling like you had to convince somebody to be against the death penalty all the time — although we always said, you know, that we are fundamentally opposed to this as a matter of policy, because this is a human rights violation.”[266] Within a few years, there were some legislative victories restricting the application of the death penalty to exclude members of some of these groups. Haines wrote in 1996:

Thirteen states and the federal system have set 18 as the age threshold for death sentencing. Despite widespread public support for the exemption of juvenile offenders, however, no state has taken action to raise its existing statutory age limit. ‘MR bills’ have fared somewhat better. In 1991, a year in which activists devoted a great deal of effort to achieving statutory provisions prohibiting the execution of mentally retarded convicts, such bills failed to pass in 15 of the 16 states where they were introduced. But eight states had enacted them by June 1993. The list grew to ten by mid-1995.[267]

Fulwood also reduced AIUSA’s emphasis on responding to announcements of execution dates with letters requesting clemency; this freed up resources to focus on proactive outreach attacking the broader institution of capital punishment, such as via the media.[268] Shortly afterwards, The Death Penalty Information Center was set up by a public relations firm with “links” to the ADPM to seek better press coverage.[269] This occurred alongside political campaigning by the NCADP in 1992[270] and other anti-death penalty advocates’ efforts to dissuade attorneys from seeking death sentences.[271] Haines argues that these developments represented a shift in the ADPM from reactive tactics to more proactive tactics.[272]

In the 1987 McCleskey v. Kemp ruling, the Supreme Court accepted that there was “a discrepancy that appears to correlate with race” but noted that unequal outcomes across races “are an inevitable part of our criminal justice system.”[273] McCleskey’s case was rejected five-to-four and Justice Lewis Powell later expressed regret at having voted against it.[274] The decreased willingness of the Supreme Court to proactively make decisions with substantial policy implications may have contributed to this decision.[275] Legal scholar John D. Bessler argues that the rejections in Gregg and McCleskey “forced death penalty opponents to open new fronts,” noting that, “death penalty foes have begun appealing directly to the American public.”[276] Other scholars have also seen the McCleskey case as a watershed moment, symbolizing a decreased interest of the Court in regulating the death penalty.[277] Indeed, legal scholars responded critically to the decision, though this may reflect their general anti-death penalty sentiment rather than the specifics of the case.[278]

In 1987 in Kansas, new emphasis by anti-death penalty advocates on the costs of implementing the death penalty may have helped to persuade the Kansas Senate to reject a death penalty reinstatement bill by 22 votes to 18.[279] The cost argument may have been influential in Alaska and Minnesota in the following years as well.[280]

Although the additional procedural requirements after Furman and Gregg had made the concern of executed innocents seem less plausible, studies from 1987 began to emphasize this risk again.[281] Several convicts were discovered to be innocent after coming close to execution in 1989-93.[282]

In 1988, Congress increased the number of offenses for which capital punishment could be used.[283] In the presidential election campaign of that year, Democratic nominee Michael Dukakis opposed the death penalty and was criticized by the Republican campaign of George H. W. Bush for his liberal views on the treatment of convicts, including his support for a prison furlough system while governor of Massachusetts.[284]

The Supreme Court rulings in Murray v. Giarratano (1989), Teague v. Lane (1989), and Coleman v. Thompson (1991) reduced the ability of those on death row to use legal defenses such as habeas corpus.[285]

A 1990 publication listed 34 national organizations and 147 state or local groups that were involved in the ADPM, either as their sole focus or as one of several causes. An additional 20 national religious organizations were listed as having official policies against the death penalty.[286] By 1991, the NCADP had $221,487 in revenue, having grown over the previous few years, and AIUSA continued to increase its budget for death penalty work.[287] Nevertheless, the movement seems to have been underfunded at both the national and state levels.[288]

Justice Brennan and Justice Marshall — the only two Supreme Court Justices to consistently oppose every judgement upholding the death sentence — retired in July 1990 and June 1991, respectively.[289]

During the 1992 presidential election campaign, Democratic candidate Bill Clinton “talked tough” on crime issues and emphasized that he had enforced the death penalty as governor of Arkansas. Clinton’s attitude contrasted with that of the previous Democratic nominee, Michael Dukakis.[290]

After the murder of a member of the congressional staff of a US senator in Washington D.C., the senator called for a referendum to reinstate capital punishment in D.C. The referendum was opposed by religious leaders and a variety of activists. The referendum was rejected by 68% of voters. In D.C., 80 of the 118 executed had been black and the majority of the voters who rejected the referendum were African Americans. Similar methods of organizing — “block parties, motorcades, and public forums” — were used again to successfully prevent death penalty legislation in 1997.[291]

In 1993, the Roman Catholic sister Helen Prejean published the book Dead Man Walking: An Eyewitness Account of the Death Penalty in the United States. The book attracted a great deal of attention and enhanced the credibility of the ADPM. Sister Prejean showed empathy for the victims of crime, making it hard for conservatives to dismiss her arguments.[292]

Lowe’s research based on The New York Times and Los Angeles Times articles shows a decline in the use of moral arguments as the primary frame in the ADPM’s public-facing statements during the 1993 to 2003 era to 37% from around 43% during the first three eras (1965 to 1992). Use of moral framings by legal advocates quoted in the sample of articles fell from 60% to 0%.[293]

In 1994, Justice Harry Blackmun — who had dissented from the majority decision in Furman to invalidate capital punishment and advocated mandatory death penalty use in Gregg v. Georgia — shifted towards opposition to the death penalty. In his dissent to the Callins v. Collins case, he renounced the court’s efforts “to develop procedural and substantive rules that would lend more than the mere appearance of fairness to the death penalty endeavor.”[294] Unlike Justices Brennan and Marshall, his opposition to capital punishment was based upon the unfairness of sentencing.[295] After his retirement, Justice Lewis F. Powell also changed his mind about his former decisions to uphold the death penalty.[296] Since they were Nixon appointees and had previously upheld the death penalty, their views could not be easily dismissed by conservatives.[297] Subsequently, Supreme Court Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Sandra Day O’Connor, and John Paul Stevens have expressed concerns with the death penalty,[298] as have many judges in lower courts.[299]

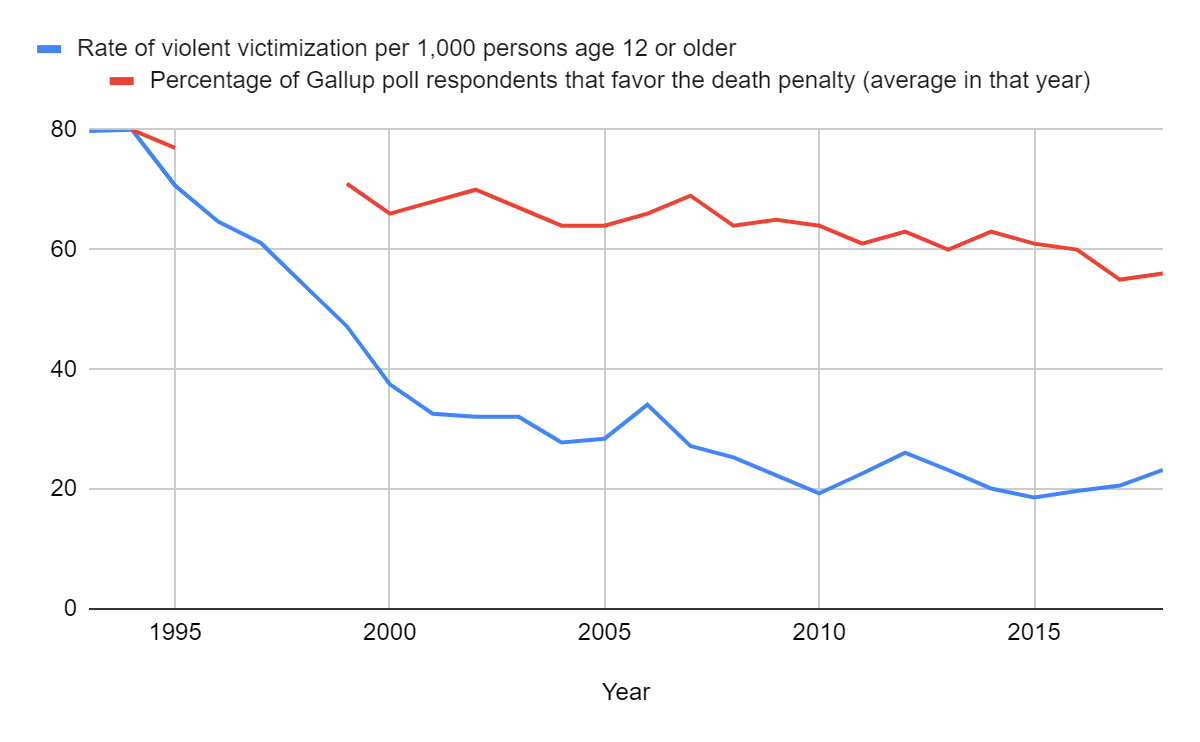

Nineteen ninety-four saw the peak of support for the use of the death penalty for murder; support subsequently fell from this peak of 80% down to 56% in 2018.[300] In the late 1990s the US economy flourished[301] and crime levels fell (see Figure 4), which may have encouraged more tolerance for convicts.[302] Indeed, support for punitive treatment of convicts seems to have declined more widely.[303] GDP per capita had been increasing in the US for decades, so this seems unlikely to have been a major factor in the change in public opinion.[304] Violent crime rates seem to have begun to decline at a nearly identical time point to the decline in support for capital punishment; the overall rate of change is different, though visual inspection suggests that even some of the temporary upticks in the two trends may be related to each other:

Figure 4: Violent crime rates and support for the death penalty.[305]

Other factors that could plausibly have played a role in the decline of support for capital punishment include:

- The publication of Helen Prejean’s Dead Man Walking.[306] However, this had occurred in 1993 and the General Social Survey found an increase in support in 1994 when compared to 1993.[307]

- The newfound opposition to the death penalty of Harry Blackmun and other Supreme Court justices,[308] though it seems unlikely that judicial opinions would be highly influential on public opinion.[309]

- The increasing and more critical newspaper coverage of the death penalty in 1996-2000,[310] including from a prolific group of journalists in Austin, Texas in the year 2000.[311] These changes in coverage could have been related to the increasing emphasis on innocence in capital punishment discussion.[312]

- A number of other highly salient events related to crime and the death penalty.[313]

In 1994, Kansas reinstated the death penalty.[314] In the same year, the New York Republican candidate for governor won the election with a pledge to reinstate the death penalty.[315] Also in 1994, politicians in Arkansas, Delaware, Illinois, Montana, Nevada, New Jersey, Oregon, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, and Tennessee expanded death penalty statutes in their respective states.[316] Between 1995 and 2006, over 20 state legislatures added new factors that made criminals eligible for the death penalty.[317]

In 1994, Congress increased the number of offenses for which capital punishment could be used.[318] In 1996, Congress passed the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act, which made the use of habeas corpus actions to protect convicts on death row more difficult.[319] Congress also reduced funding for organizations that provided legal advocacy for convicts, including convicts contesting their death sentences.[320] The 1994 and 1996 acts were signed into law by President Clinton, a Democrat, and advertised as successes in his 1996 reelection campaign.[321]

By the mid-1990s, the Council of Europe had made the commitment to abolishing the death penalty except in times of war a condition for new countries to join.[322]

A paper by political scientists Frank E. Dardis, Frank R. Baumgartner, Amber E. Boydstun, Suzanna De Boef, and Fuyuan Shen quantified articles in The New York Times by “innocence,” “constitutionality,” “morality,” or “other” frames; it found that from 1996, there was a rapid increase in the number of NYT articles on capital punishment (rising to nearly 250 in 2000, higher than the previous peak in 1977), the hostility of the articles towards capital punishment, and the proportion of articles that used an innocence frame.[323] Three of the same authors — Baumgartner, De Boef, and Boydstun — found in their book that there was also an increase in hostility, coverage, and usage of the innocence frame in magazine articles.[324] Their analysis of other newspapers suggests that there was a rise in innocence framings from around 1998.[325] They argue that the surge in media attention to the death penalty was due to “a larger social cascade surrounding the new innocence frame.”[326]

1997-present: Growth of the moratorium movement and sporadic legislative success

Since the 1960s, United Nations institutions such as the Human Rights Committee had recommended that nations with the death penalty consider implementing moratoriums. Suggested resolutions by the UN General Assembly in 1994 and 1999 called again for an international moratorium on capital punishment, though a resolution was not passed until 2007. This non-binding resolution asked UN member states to increasingly restrict the death penalty while ensuring that international standards were met.[327]

In 1997, the American Bar Association (ABA) passed a resolution calling for a national moratorium on executions until state legislation complied with the ABA’s guidelines.[328] This brought media attention and non-partisan credibility to the anti-death penalty cause.[329] Two years subsequently, the ABA claimed that their resolution “had a profound impact… in spawning grassroots efforts questioning the fairness of the death penalty as implemented in particular jurisdictions.”[330] In October, 2000, the ABA ran a conference on the death penalty.[331] In September 2001, the ABA set up its Death Penalty Moratorium Implementation Project, which encouraged state governments and other bar associations to press for moratoriums on capital punishment.[332] In 2017, the ABA noted that, “[a]t least ninety-nine local jurisdictions; many dozens of organizations; and thirty-six national, state, local, and specialty bar associations have passed resolutions supporting moratoriums in their jurisdictions.”[333]

In 1998, the National Conference on Wrongful Convictions and the Death Penalty was held in Chicago. It was organized by Lawrence Marshall, a law professor at the Northwestern University. According to a contemporary news article, the conference was attended “by more than 1,000 lawyers, law students, professors and death penalty opponents” and included “28 of the 73 men and 2 women who [had] been released from death rows across the country since 1972.”[334] Marshall subsequently claimed that the conference made wrongful convictions into a key talking point in the movement.[335]

In 1998, four states introduced bills to abolish the death penalty. Twelve states introduced bills in 1999.[336] The ABA notes that by July 2001, “bills specifically calling for a moratorium [were] introduced in 17 states, and legislation to address death penalty-related concerns raised in the ABA moratorium resolution [were] introduced in 37 of the 38 states that authorized capital punishment.”[337] In 2001, Nevada and Maryland nearly passed bills for moratoriums.[338] Additionally, local organizations and communities passed resolutions calling for moratoriums.[339]

The death of gay student Matthew Shepard prompted some members of the LGBTQ community to voice support for the death penalty.[340] Nevertheless, other members of the LGBTQ community have opposed the death penalty for a number of reasons, including concerns about homophobic discrimination in sentencing,[341] and at least 11 groups publicly announced their opposition to the death penalty during Shepard’s murder prosecution.[342] LGBTQ groups have subsequently engaged in some anti-death penalty advocacy. For example, the group Queer to the Left used a letter-writing campaign to encourage the commutation of the sentences of all death row inmates in Illinois in 2002 and a press conference and newspaper ad to mobilize the LGBTQ community on the issue.[343]

In 1999, Nebraska’s legislature voted for a moratorium on the death penalty, but the governor, Mike Johanns, vetoed the bill.[344] Though it did not override the veto on moratorium legislation, the legislature unanimously overrode Johanns’ veto of funding for a study on the fairness of the death penalty in Nebraska.[345]

The Illinois House of Representatives passed a nonbinding moratorium bill in 1999.[346] In 2000, the Republican Governor, George Ryan, imposed a statewide moratorium on executions and subsequently granted clemency to all prisoners on Illinois’ death row.[347] Kirchmeier believes that this was “not based on a moral opposition to the death penalty but rather on concerns about systemic problems.”[348] These concerns had been encouraged by publicity and advocacy around recent exonerations and executions of convicts whose guilt was in question, especially by the Chicago Tribune newspaper and the law professor Lawrence Marshall.[349] Ryan justified his decision by stating that, “[o]ur capital system is haunted by the demon of error—error in determining guilt, and error in determining who among the guilty deserves to die.”[350] In a poll, 66% of Illinois residents supported his moratorium decision.[351]